In conjunction with the Book of Happiness, we already pointed out the importance of being attentive to small events. And it is most likely the minor moments leaders notice that motivate their employees the most, inspiring them to perform well. Praising or acknowledging fruitful efforts can work wonders.

“Praise is more effective and has a longer-lasting impact. Co-workers receiving praise set their sights higher, to justify the praise. The brain’s biochemical reaction is interesting: Praise causes a flood of dopamine to be distributed, which the brain perceives as a positive event and stores it away in its long-term memory. […] Motivated and enthusiastic people are more productive, develop better solutions, and radiate positivity, which draws attractive customers.”[1]

All the same, leaders are often exceedingly reluctant to praise their employees. “Do I really need to praise and acknowledge things that should be taken for granted? I mean, even tasks that are covered in the employment agreement?” These are frequent questions during coaching sessions.

And yet, it is the same leaders who expect more from their employees than the contract demands. If the only reward for extra effort is criticism when something goes wrong, you have little right to complain about unmotivated and disgruntled co-workers.

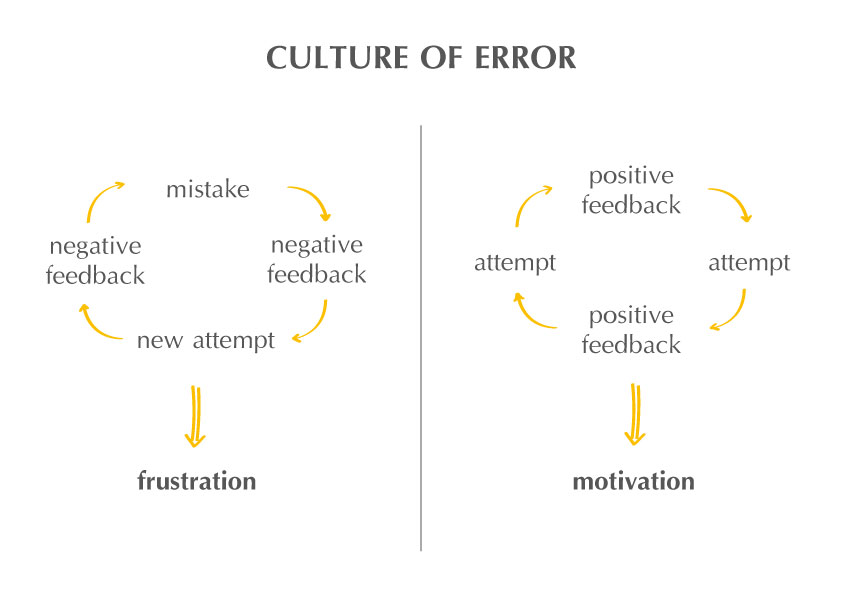

This culture of errors is especially widespread in Germany. An adeptly accomplished task is taken for granted as no big deal, while mistakes are mountains made of mole hills and discussed, deliberated and analyzed to a pulp. When I create a non-appreciative professional environment, i.e. hyper-critical, obsessed with control, I inevitably set up barriers, blocking all avenues to success. A negative culture of errors leads implacably to stress, pressure and overextension, smothering in the cradle any resourcefulness or self-initiative.

This is compounded by the fact that 98% of our language usage zeros in on errors. In nearly all of our exchanges, we express negations. We articulate what we don’t want instead of clearly describing what we imagine things should be. […]

(The answer is easy.) Since we think in images, our brain cannot process negations. The word didn’t, doesn’t make it to the top shelf. You probably know the pink elephant phenomenon. If you’re told not to think of pink elephants, you can’t think of anything else.

Now, transfer this insight onto your everyday professional routine. If I tell an employee not to run, then I shouldn’t be surprised when he doesn’t move at all. Or when one of my workers comes 15 minutes late every day and I tell him, “Don’t you dare come in late tomorrow or you’re fired.” So, on the following day, when the chronically late worker is once more running late, he will call in sick instead of risking losing his job. The actual problem is neither approached nor solved.

His boss should point out the worker’s tardiness using a positive formulation, “Make sure to get up 15 minutes earlier tomorrow, so you can be on time for work.” Now, the employee has the option to react by taking his boss’s suggestion to heart or talking to him. It is also possible that the worker’s tardiness has a more complex reason. […]

An excerpt from the book “Leadership Is Not an Illusion – A wealth of adventure, experiences and stories to tell 20 years of consultancy practice” written by Gianni, Jan & Marcello Liscia, 2020

[1] it.de, Glück ist ein Wirtschaftsfaktor / Happiness is an economic factor, 09.01.2015.